| Overview & Diagnosis > Overview of PPP experience | Role of PPP |

Application of PPP

Application of PPP

|

In the early 1990s there were expectations that the private sector would play a substantially more significant role in the provision of transport infrastructure and services. Some of these expectations, especially regarding infrastructure, were impractical, and the authors of Sustainable Transport (World Bank 1996), while supporting an expanded role for the private sector, were cautious about the extent to which the private sector could increase its role. |

The key objective of an infrastructure program is to meet the public's social and economic requirements in a cost effective manner.

PPP have a place in fulfilling this objective by providing for an in-built incentive system which injects the discipline and motivation of the marketplace into infrastructure investment policies.

However, public-private partnerships are not, and probably never will be, the dominant method of infrastructure acquisition. They are too complex, and costly, and for many small projects constitute "using a sledgehammer to crack a nut". In some cases, they may be beyond the capacity of the public sector agency to implement and manage. For other projects, the tight specification of the outputs required may be difficult to detail for an extended period.

Moreover, lower income developing countries will need continued application before PPP programs may be initiated and a gradual step-by-step process applied to increase their share of the total investment portfolio of a given public highway network.

Where is PPP appropriate?

There is wide acceptance that the role of PPP is to complement rather than replace conventional public sector procurement. PPP cannot pretend to represent the best solution for numerous low volume roads and local contracts implemented at local and regional level in developing and even industrialized countries. To attempt to do so would be counter-productive to efforts to develop PPP on a national scale.

It is widely recognized that a pragmatic approach should be adopted to PPP as opposed to an approach based on political dogma and the absolute virtues of the private sector. It is thus advisable to target those specific projects where PPP could offer significant value for money and also mobilize additional resources unavailable to the public sector.

Conventional procurement should be preferred if the quality of the infrastructure can be clearly specified, whereas the quality of the service cannot. In contrast, PPP is better if the quality of the service can be well specified in the initial contract (or more specifically, there are good performance indicators that can be used to reward or penalize the service provider), whereas the quality of the infrastructure cannot (Hart, 2003)

PPP seem likely to be appropriate if:

- Service outcomes can be clearly specified and measured

- There exists the potential, and the incentives to introduce, design innovations and operational changes that can raise efficiency

- Payment mechanisms are devised that give the operators the motivation to maintain service quality

- Value for money is able to be demonstrated, after allowing for costs of project development and costs of monitoring the contract

- An integrated service can be provided with close working relationships and good communication between service providers

- There are transparent accountability procedures and a due regard for the public interest

PPP and conventional procurement

It is generally recognized that the proportion of investment procured through PPP within mature PPP markets is around 15% of total investment. As a result, 85% of public sector procurement would continue to be procured through conventional methods.

If we look at road funding, the picture is similar. Worldwide, government budgets currently finance 95% of investment in the road network, while less than 5% is financed directly through tolls (ie direct charges by the user). In the USA, the picture is similar with tolls currently providing only 8% of all U.S. highway revenue.

Paradoxically, if we consider funding collected by governments from road users, in the form of road user taxes (principally fuel taxes), governments are receiving from the road sector much more than they are giving back. We can estimate that governments in developing countries, as in the European Union, siphon off about 2/3 of road user taxes to the general budget and re-invest only a 1/3 in better roads. However, the scale and ease in mobilizing fuel taxes, current environmental concerns and green-house gas limitations and political pressures on the use of public funds make any increase in the allocation to highway budgets very unlikely.

| PFI is intended to continue playing a small but important role in the overall objective of delivering modernized public services. It will continue to be used only where it can demonstrate better value for money [than other forms of public procurement] and is likely to continue to comprise around 10-15 per cent of total investment in public services. The vast majority of investment in the UK's public services shall continue to be conventionally procured.

As a result of constraints to increased PPP investment and the required reforms and policy directives, it is unlikely that this proportion would increase in the short-term. Traditional public sector contracts will remain the predominant source of investment in developed and developing countries alike. It is therefore important to target the use of PPP procurement to those applications where it can be used most effectively.

|

This result is also being observed in developing countries as a result of constraints on the development of PPP.

|

At the broadest level, the review finds that the strategy suggested in the WDR [World Development Report, World Bank, 1994] has stood the test of time in OECD countries. In developing countries there is also evidence that greater involvement of the private sector, especially in service provision, usually leads to a significant improvement in transport sector performance. Nevertheless, for the foreseeable future, the public sector in developing countries will remain the principal provider of infrastructure because of investment risk factors and public ownership issues. |

China, with the most extensive toll network in the world (20,000 km) and the largest PPP market in developing countries until 2006 applies PPP procurement for an estimated 6-9% of its total highway investments (estimate from the late 1990s, World Bank, A Decade of Action in Transport; 2007).

In Africa, the picture is similar. PPP investments are estimated to have provided 10-15% of total infrastructure investment over the past twenty years in African countries (Estache and Yepes, 2004). Moreover, whilst significant increased investments are planned in the highways sector, the emphasis on private sector funding in the 1980s and 1990s has been criticized as being a policy mistake.

In Africa, a more pragmatic approach to PPP is being adopted by a better orientationof the nature and scale of its contribution to infrastructure development.

|

Despite its clear benefits, African governments and development partners sharply reduced, over the 1990s, the share of resources allocated to infrastructure – reflecting its lower priority in policy discussions. In retrospect, this was a serious policy mistake, driven by the international community that undermined growth prospects and generated a substantial backlog of investment – a backlog that will take strong action, over an extended period, to overcome. This was a policy mistake founded in a new dogma of the 1980s and 1990s asserting that infrastructure would now be financed by the private sector. Throughout the developing world, and particularly in Africa, the private sector is unlikely to finance more than a quarter of the major infrastructure investment needs. Between 1990 and 2002, relative to total infrastructure investment in the order of USD 150 billion, private commitments for infrastructure in sub-Saharan Africa totalled only USD 27.8 billion, and two-thirds of this amount (USD 18.5 billion) was for telecommunications. Recommendation: Africa needs an additional USD 20 billion a year investment in infrastructure. This is equivalent to at least a doubling of expenditure on infrastructure. It is not our view that an increase of USD 20 billion could be easily absorbed effectively over the next five years. The priority is to deliver the extra USD 10 billion a year – using existing institutions while improving local capacities to manage increasing resources – and then review the potential for further expansion. The necessary expansion is on a scale that means that in the short-term only a small fraction could be funded by African public finances. Experience has told us that only a small fraction will come from the large private sector operators unless donor countries are willing to support them through guarantees and other insurance-type schemes. Over time, and on the basis of economic growth and with improvements to investment climates, financing could increasingly come from domestic public finances, the private sector and user charges (where appropriate and equitable). The funding should also support a pragmatic approach to private sector participation that recognises the roles where the private sector can add most value – most often as a performance-based contractor in building, delivery and maintenance. It should also build on existing initiatives to attract much-needed private sector investment, such as the Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF), the Municipal Infrastructure Investment Unit (MIIU), the work of the International Finance Corporation, and the programs of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG). These work with national and municipal governments to improve the investment climate, develop commercially viable projects, and provide funding including in the form of long-term debt finance and guarantees to cover the risks of local currency financing. The importance of developing and promoting public-private partnerships for infrastructure was emphasised in the Commission's business consultations. The need for governments to ensure that the regulatory environment is in place to facilitate private sector investment in ICT was also highlighted. So too was the importance of a co-ordinated, continent-wide approach to ICT that brings together donors, governments and the private sector to enhance Africa's connectivity. Innovative private sector approaches to meeting the infrastructure needs of poor people – such as rural electrification – are one focus of the Growing Sustainable Business Initiative. Involving the private sector in setting infrastructure priorities is a focus of the Investment Climate Facility. A shortage in the supply of bankable projects is a critical constraint in attracting private investment. The fund should support the expansion of the NEPAD Infrastructure Project Preparation Facility, hosted and managed by the ADB and other such initiatives. Of course this is an issue that faces public projects too: building public sector capacity is also key.

|

Some countries however suggest a higher rate of PPP investments, notably India and Chile, which may suggest that a higher role for PPP is possible to fund major highway investment programs subject to a suitable enabling environment.

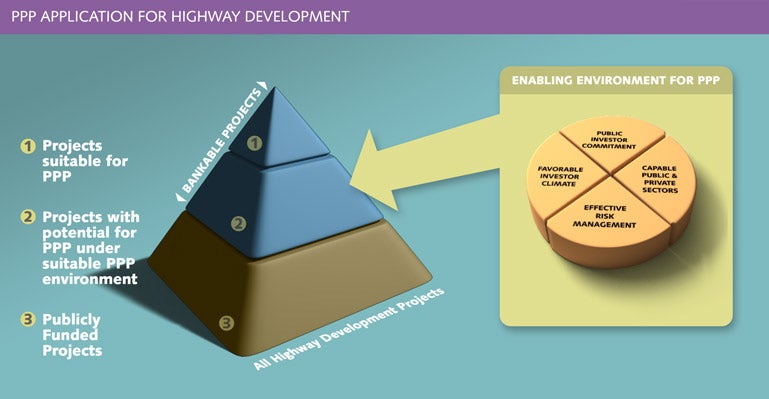

The application of PPP in highway development is represented in the figure below. At the tip of the pyramid, only a small number of highway projects can generate enough secure income to be self-financing and feasible under a PPP option. These are considered as bankable projects for PPP. However, the vast majority could not pay for themselves and could only be built under conventional public procurement.

However, the subsequent band of projects could also attract private investment provided the public sector can establish a suitable enabling environment for PPP. If the government wishes to capitalize on the dynamism of the private sector in meeting the needs of its highway sector, it is the public sector's responsibility to make projects bankable. It may thus lower the bar to the PPP solution.

PPP programs should be seen as complementing and not replacing conventional procurement methods.