| Tools > Case Studies | Marginal Projects |

Country case study: France

WHY READ THIS CASE STUDY?

|

Case study description

Introduction

The toll motorway concession system initiated in France in 1955 is now over 8,200 km long, and constitutes over three quarters of the 10,800-km-long motorway network, the remaining quarter being toll-free. The entire paved road network in France is 1,000,000 km long. Most of this network falls under the responsibility of local authorities as anticipated by decentralization policies.

The government is in charge of 20,000 km including:

- 8,200 km of tolled motorways operated in concession

- 2,600 km of toll free motorways (urban ring roads)

- 9,200 km of toll free trunk roads (main axis considered as strategic)

The motorway network, which constitutes 1% of the total length, accommodates 25% of the national traffic.

| Privatized companies | |

| ASF | 2504km |

| APRR | 1821km |

| SANEF | 1374km |

| SAPN | 368km |

| AREA | 384km |

| ESCOTA | 460km |

| Private companies | |

| COFIROUTE | 985km |

| SMTPC (Prado-Carénage) | 2,5km |

| Viaduc de MILLAU | 3,7km |

| ALIS | 125km |

| ARCOUR | Under construction |

| ROUTALIS | Under construction |

| ADELAC | Under construction |

| Public companies operating tunnels, bridges and urban ring roads |

|

| ATMB | 118km |

| SFTRF | 80km |

| CCI du Havre | 7km |

| COURLY-EPERLY | 10km |

Source: French Road Administration

Toll motorways operating in France

France has experimented with both toll and non-toll financing as well as with publicly and privately-owned toll roads in building its motorway system. The construction, maintenance and operation of the national road network is financed through the national budget (25% of total resources), regional budget grants to the national network (20%), and toll motorway concession companies' resources (50%).

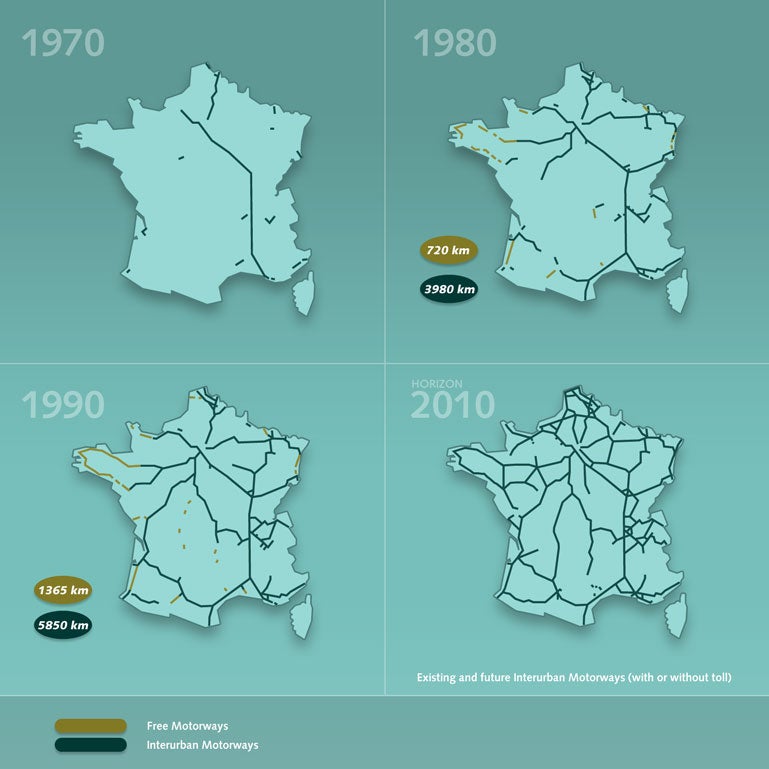

The density of the French motorway network is about 16 km per 1000 square km and 130 km per million inhabitants. The French toll motorway system began in the 1950s and went throughfour main periods of development as presented hereafter.

Evolution of the toll road network system

1955-1969: a commitment to tolls with public companies

In the 1950s most rebuilding after World War II damage was over and car-ownership began to increase rapidly (200 cars per 1000 inhabitants in 1966). By 1951, the Government had established a dedicated road fund (FSIR) which was to receive a percentage of motor fuel tax receipts, but competing budgetary pressure prevented the Government from funding the FSIR in full. In 1955, therefore, a law was passed to allow motorways to be financed from tolls. Public control was to be maintained by granting concessions only to a local public organization, a Chamber of Commerce (a public body in France) or a semi-public company in which public interests had a majority shareholding.

The 1955 law stated that, in principle, motorways are free. However, the exception rapidly became the rule, since within a decade, between 1956 and 1963, five semi-public companies were set up. These companies were called semi-public motorway concession companies ("sociétés d'économie mixte concessionnaires d'autoroutes") or "SEMCAs". The initial concessions were only for short portions of motorway, 50 to 70 km, except, in 1963, for the top priority north-south route between Lille, Paris and Lyon with 130- and 160-km segments.

All five SEMCAs shared a similar financial and organizational structure: they had very low capital (USD 100,000 to USD 300,000) and share-holders were public bodies only. The national equity stake was held by the Caisse des Dépots et Consignations (CDC), a State-owned investment bank.

The Government provided initial financial assistance by guaranteeing the loans of the SEMCAs and providing fairly significant amounts of cash and advances (averaging 30 to 40% of construction costs). Throughout the 1960s, the SEMCAs were little more than paper organizations, nothing more than the "false nose of the State" as one Minister said:

- a State-owned investment bank (CDC) marketed the State-guaranteed loans for the SEMCAs through a special office established in 1963, Caisse Nationale des Autoroutes (CNA), which pooled the funds borrowed by the SEMCAs;

- another subsidiary of the CDC, SCET, managed the accounts and construction contracts;

- the Road Authority in the Department of Public Works and Transport designed and operated the motorways (except for toll collection). Private contractors built them.

1970-1981: liberalization and privatization, the emergence of cross-subsidization

At the end of the 1960s, only 1,125 km of intercity motorways were in service. A reform was set up in order to (i) allow private companies to compete for new concessions and (ii) strengthen the existing SEMCAs, to give them greater autonomy and responsibility.

Between 1970 and 1973, four private toll road companies were awarded contracts for between 300 and 500 km of motorway each (except for one 63-km-long concession). All four new concessionaires were consortia of major French public works companies. No investors were interested in investments with such a long payback period and banks are said to have taken out shares more because they wanted to support contractors with which they had links and to issue bonds rather than because they wanted to invest.

The Government was less generous with assistance for concessions granted in the 1970s than it had been in the 1960s. Nevertheless, significant financial aid remained available to both private and SEMCA concessions. For example, for the first private company, COFIROUTE, 10% of the funds were covered by equity, 10% by in-kind advances from the State, 65% by State-guaranteed loans and 15% by loans without guarantee, i.e., 75% of the funds were provided or backed by the Government.

At the same time, the SEMCAs, with SCET, established a new company, SCETAUROUTE (nowadays Egis route), to act as their "maître d'oeuvre" (Engineer), their engineering firm and prime contractor for construction and research into motorways. The SEMCAs created their own maintenance services.

Increasingly the motorway companies were expected to subsidize new stretches with surpluses generated from their older segments which had higher traffic and had been built at lower cost. Moreover the dates at which the concessions on these older and more lucrative sections expired would often be extended. A system of cross-subsidization within companies gradually emerged. It undermined the concept of profitability of the individual motorway segments and even of the company (for SEMCAs).

Lastly, the concession agreement of the four private companies stated that toll rates would be set by the company within the limits determined in the concession agreements. This procedure was extended to the SEMCAs. However, in 1975, the Ministry of Finance declared that it would regulate tolls. Tolls returned firmly under the authority of the Ministry of Finance thus enabling it to control the entire toll motorway system.

1982-1994: facing the crisis, a nation wide mechanism of cross-subsidization

At the beginning of the 80's the motorway system faced serious cash deficit problems, one reason for which was the oil crisis. The State took over three out of the four private companies and indemnified shareholders, which was a soft enforcement of the forfeiture clause.

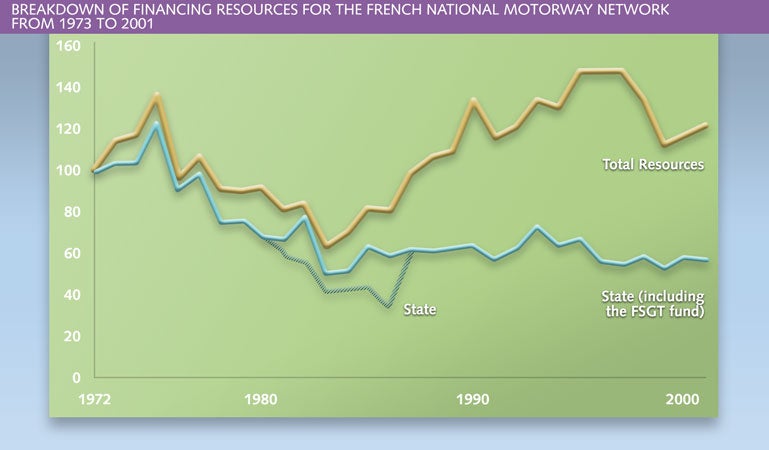

In 1982 the Government established a new dedicated fund, the FSGT (Special Fund for Public Works) in replacement of the FSIR. This fund was allowed to issue bonds to give a leverage effect to the additional tax on top of fuel tax, which was earmarked for it. On average, public resources dedicated to roads (budget + FSGT) were stable during the existence of this Fund, until 1987, when the FSGT's increasing resources were compensated by decreasing budget funds, as shown in the figure below.

Evolution of road financing in France

In 1982, a new Government Agency, Autoroutes de France (ADF), was set up to serve as a clearing house for issuing new advances to and receiving repayment of former advances from the SEMCAs. ADF allowed the Government to authorize cross-subsidies among companies (as well as within companies as had occurred since the mid 1970s).

In 1987, the Government announced its intention of strengthening ADF with a capital injection of about EURO 300 million which ADF could use to make advances to the SEMCAs and increase the State's equity. This capital injection, made by tapping funds generated by the privatization of public-owned companies, strengthened central Government control over the SEMCAs.

By the late 1980s both local and national Governments began to discuss the possibility of new private concessions on a non-recourse basis, especially in urban areas, and projects were implemented, for instance, in Marseille (Prado-Carénage Tunnel).

1994-2000: contractualization and consolidation within the public sector; improvement of competition

Since 1994, multi-year investment contracts have been implemented. These contracts create a balance between investment and toll increases and provide certainty to concessionaires for a five-year period. The public companies have been consolidated into three main groups in order to gain in terms of geographical coherence and financial viability. Parallel to this consolidation, there was an increase in capital (from about USD 4 million to USD 150 million). As of 2000, the different concessionaire companies involved in the motorway sector in France, and the respective networks under their responsibility were the following: (i) SANEF (1,254 km); (ii) SAPN (366 km); (iii) SAPRR (1,768 km); (iv) AREA (382km); (v) ASF (1,996 km); (vi) ESCOTA (460); (vii) Cofiroute (798 km); (viii) ATMB (107 km); and (ix) STRF (55km).

Until 1998 each new stretch was conceded to an existing company (public or private) and this new stretch was merged into the global concession contract, the terms of which (especially duration) were globally renegotiated. In 2000 a final extension to the concession period (which constitutes State aid according to the European Community treaty) was negotiated with the European Commission (European Commission letter SG (2000) D/ 107823 dated October 10, 2000). In compensation, each new concession will be a stand-alone project.

Since 2000: privatization of concessionaires

In the begin of the years 2000, the toll motorways policy has known important changes in order to improve, according to the general European orientations to improve efficiency. First, from now on, concessions are granted after publicity and no more directly backed by collateral. Secondly the accounting regime of the present concessions has been made more in line with the common one (the core question was the depreciation process), and the State gave up the guarantee for liabilities to existing concessions; in compensation, the duration of the concessions was increased; this State aid was agreed by the European Commission (State aid n° N540/2000). As a consequence (linear depreciation on a longer period of time) the companies, without any change in their cash flows, have produced positive results, paid income tax and distributed dividends.

Thirdly tolls have been made subject to VAT (CJEC case C-276/97, Judgment of 12/09/2000, Commission / France) for when use of the road depends on payment of a toll, the amount of which varies inter alia according to the category of vehicle used and the distance covered, there is, therefore, a direct and necessary link between the service provided and the financial consideration received.

Since 2000 the new concessions have been granted to private firms through this transparent procedure.

In 2002, the main public motorway company, ASF was introduced on Euronext, the State retaining 51% of the shares, the rest being floated in the stock market. In the same orientation, the motorway firms adopted a more aggressive commercial policy, based on tariff differentiation (discount fares, season tickets, subsidies from local authorities for discount rates to the local users, ...). SAPRR has been introduced on Euronext in December 2004 through the flotation of 30% new shares and SANEF floated quickly in similar conditions.

In May 2005, the French government decided on the total privatization of ASF, SANEF and APRR and the process was achieved early 2006 with the sale of these concessionnaire companies to international and nationals banks, insurance companies, contractors and infrastructure funds. It must be stressed that the shares have been sold to private sector, i.e. the concession companies privatized, but that the facilities remain public property.

Conclusions

Eventually, the French system has moved from an administrative one based on "quasi non-autonomous" organizations to privatized companies concessionaires of public utilities. The last move was based on the French government's need of immediate cash but the rationale has remained an operational one more than a pure financial one.

The scheme of the French motorway system development has changed many times since 1955 but one principle always remains: the motorway cost recovery is based on the toll collection. In other words, the willingness to pay tolls of the road users was never lost, whatever the liberalization, nationalization or privatization of the system.

But today it can be expected that the toll collection system has reached an end in France. Actually, the French motorway network is "mature": the most interurban socio-economical advantageous motorways have been built. The Ministry of Transportation since October 2007 with the meeting called "Grenelle de l'Environnement" started a big curve towards sustainable development and the priority in land infrastructure development is given to the railways. Therefore the challenge faced by the French motorways is not to extend its length but to face up the congested sections mainly in urban areas where there are no tolls!

In order to allow new ways to involve private finance in motorway projects without relying on direct tolls a new law to develop PPP was voted on June 17, 2004 (n° 2004-559) and amended in 2008. This law is supposed to foster the development of PPP for motorways projects since it will allow a private partner to recover its costs without tolls (shadow toll, availability payment, etc.). The first law was not really a success since only two road projects had been financed based on new PPP schemes. It remains to be seen whether the amendment will help to start new kind of motorway PPP in France.

![]() Annual Report 2006, Association of French Motorway Companies (ASFA)

Annual Report 2006, Association of French Motorway Companies (ASFA)

![]() Annual Report 2006; National Motorway Fund of France

Annual Report 2006; National Motorway Fund of France

Association of French Motorway Companies (ASFA). http://www.autoroutes.fr/en/homepage.html

National Motorway Fund of France. http://www.cna-autoroutes.com/default.htm